|

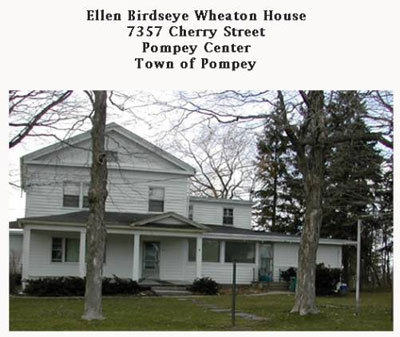

Ellen Birdseye Wheaton Home

7357 Cherry Street

Pompey Center

Town of Pompey

1818

The Ellen Birdseye Wheaton girlhood home symbolizes the lives of many European American abolitionist women whose commitment to reform was rooted in a New England Congregationalist tradition. It also suggests the ways in which many women balanced public reform work with the demands of raising a family.

Ellen Birdseye Wheaton is best-known for a diary she kept from 1850 to 1858, detailing her life as the wife of Charles A. Wheaton, abolitionist, hardware merchant, and railroad speculator, and as the mother of twelve children. Privately printed as The Diary of Ellen Birdeye Wheaton (Boston, 1923), it contains a detailed account of Ellen Wheaton’s family, social, and reform activities. Selections from this diary were reprinted in the Post-Standard in March 2002.

Ellen Birdseye was born in 1816 in Pompey, New York. Her father, Victory Birdsye, was a lawyer, district attorney for Onondaga County, member of the New York State Assembly, and for two terms a member of Congress. Although Ellen Birdseye could not follow her brothers to Yale University, she was well-educated for a woman of her time, first at Pompey Academy and then at schools in Cortland and Albany. She married Charles A. Wheaton, also of Pompey, in 1834, and the couple moved to Syracuse a year later. Ambitious and resourceful, Charles A. Wheaton became a very successful businessman and reformer, building the Wheaton Block at the corner of South Salina and Water Streets, until he lost his fortune in in an attempt to create a railroad from Charleston, S.C., to Knoxville, Tennesee in 1854.

Ellen Birdseye Wheaton and her husband shared abolitionist sympathies. Charles A. Wheaton was so active in public anti-slavery activism that one of his employees thought he must be the president of the underground railroad. William “Jerry” Henry valued Wheaton’s assistance so much that he sent him a carved hickory cane with a deer horn handle from Kingston as a thank-you present.

Ellen Birdseye Wheaton had heavy family responsibilities, and, as a woman, her activism was less publicly obvious than that of her husband. The couple had twelve children, some of whom they sent to a school run by Theodore Weld and Angelina Grimke Weld, abolitionists and woman’s rights advocates, in New Jersey. In her diary, Ellen commented astutely on such events as the rescue of Harriet Powell, Frederick Douglass’s speeches, anti-slavery conventions in Syracuse, the rescue of William “Jerry” Henry, the Fugitive Slave Law, and the emerging woman’s rights movement.

Ellen Birdseye Wheaton died suddenly in December, 1858, the day after the marriage of her eldest daughter.

The Ellen Birdseye Wheaton house is a two-story gable-and-wing building with a porch across the front. The wing on the north was enlarged in 1881, according to Pompey: Our Town in Profile. The original south wing was later detached. Windows, siding, and front porch have been changed, perhaps in 1944, when the house was remodeled for use as a restaurant.

While Charles A. Wheaton’s boyhood home may still exist in Pompey, none of the Wheaton houses in Syracuse’s is extant.

Bruce. Dwight H., ed. Onondaga’s Centennial, Vol. I. Boston History Company,

1896, 353-54.

The Diary of Ellen Birdeye Wheaton, with notes by Donald Gordon. Boston, 1923.

Sara Errington, Articles in Post-Standard, March 2002

Onondaga Landmarks. Syracuse: Cultural Resources Council of Syracuse and

Onondaga County, 1975.

Pompey: Our Town in Profile (Pompey: Township of Pompey, 1976), 115-6.

Conversation with Sylvia Shoebridge, Pompey Town Historian

Research in church records, especially Congregational Church records might reveal more about Ellen Birdseye Wheaton’s life. Manuscript census records for 1850 and 1855 would give some indication of the size and composition of their household. Did it include people who may have been freedom seekers?

Click on picture to enlarge